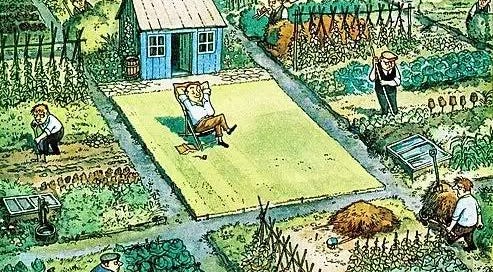

I really liked this article (illustrated with a great Thelwell cartoon) I saw on LinkedIn a while back because it underscores Coburn Ventures' "magisterial inactivity" concept.

Pip Coburn says:

"In our investment process, when our performance hits a bad patch, we intentionally direct energy in a mini-offsite toward broadly examining our process…as opposed to reacting in a devolved form by making trades that generate very short-term, personal “doing” relief, with perhaps zero positive actual effect on clients’ money. We go so far as to make sure that our mini-offsite on process is NOT directed in any way toward “solving” the near-term so-called “problem.” We sometimes are trained to be so active as problem-solvers that we can be prone to mistake the very nature of something with a problem. In investing, often a “bad patch of performance” is part of the nature of the activity of investing, as opposed to there being a “problem.” Watching our daily (or weekly, monthly, quarterly) performance is a complete timing mismatch for “investing,” even if others (consultants) demand we explain and fix it!!!"

Simon Evan-Cook’s article says:

"[T]he temptation to end the pain of disdain is huge: Maybe you’ll give in and buy the big, obvious companies, or maybe you’ll quit your job (if you haven’t already been sacked). Either would bring sweet relief from being reminded, every single day, that the world thinks you’re a clown. However, Sod’s Law rules: Inevitably, the moment you give up on your one thing, is the moment it dramatically rebounds. While the thing you’ve just capitulated into crashes (big, obvious companies had a nightmare last year). Now, if I (or you) pick managers who say they only do one thing, but stop doing it after a tough year or two, I’m stuffed. It means I’m spending too much time exposed to their one thing when it’s not working, and not enough time when it is. This is why I’m drawn to Deck-Chair dude. He’s comfortable being different to everyone else. Like Buffett; he knows what he wants, and he knows how to get it. So he’s ignoring everyone else, and their disapproving glares, and focusing on doing his one thing. So, as long as neither of us buckle (and that we’re both good at our respective one things that work over the long term), we’ll do OK."

Later, I read in The Economist:

"Higher costs would not matter if the trading decisions of the fund managers were sufficiently astute. But that is not the case. When the academics compared the returns of the funds with their estimated trading costs, the funds with the highest costs had the lowest returns. The return gap between the highest- and lowest-cost quintile was 1.78 percentage points a year. Although excessive trading has been shown to dent returns, fund managers have become more active, not less, over time. In the 1950s average mutual-fund turnover was 15%; by 2011 it was around 100%. By contrast, a different academic study shows that private investors do seem to learn the trading lesson."

So don’t just do something, sit there!

I stumbled across more evidence that "magesterial inactivity" https://gunnarmiller.substack.com/p/magisterial-inactivity appears to work a lot better than conventional wisdom would assume https://www.ft.com/content/651cc7a4-27e3-4026-9381-76421a0203bb "How many assets do you really need in your long-term portfolio? In principle, you do not really need more than two: a global equity fund and a broad bond fund in your own currency, with the relative amounts a function of your return needs, ability to withstand short-term drawdowns, and need to control long-term risk on your ultimate portfolio. This gives you very good diversification, clarity and simplicity on what you are holding, and high liquidity with minimum costs if held through passive funds, mutual or exchange traded (ETFs). One could argue that your bond fund should be global, but that would add foreign-currency risk that is generally not well compensated. If you then have strong views on what asset types, countries, or sectors to have more of than is in these broad funds — say you fancy Technology — you can simply add a Tech ETF to these two funds. It is harder when there are certain assets you want to have less of, or not have at all — say oil companies. You would need a fund that excludes oil companies, but that may not exist if there are not enough investors like you who do not want to hold oil. If such a fund does not exist, then you will have to build a portfolio bottom up by trying to buy all the other sectors, for which funds will surely not all be available. Hence, it is much easier to execute overweights than underweights in a simple portfolio. In short, you will do quite well with holding only two funds: a global equity one and a local bond one."

This also says something interesting about commodities: "Nearly everyone should just buy a cheap global equities fund for diversification and a locally denominated corporate bond fund to minimise FX volatility, he says. Government bonds are only useful for managing drawdown requirements, so they have no place in your long-term strategy. Commodities don’t generate income so it’s probably not worth bothering with them either, unless you have strong feelings about extreme climate change or have some specific risk to hedge."